Hey everyone! Welcome back to the blog. This blog post today is gonna be a boozy one. A couple weeks ago I went out in search of blackthorn berries — better known as “sloes” — to make traditional British sloe gin.

Gin is a very popular alcoholic drink in the UK. Actually, most alcohol is popular here. But that’s besides the point. At some point during in the 17th century, one British guy had the idea of dunking blackthorn berries in gin. Was he feeling a bit tipsy when he came up with that? Maybe. Am I still going to try it? Absolutely.

You can’t make sloe gin without sloes, so that’s probably the best place to start.

Sloes grow on the blackthorn shrub (Prunus spinosa).

If you want to know why it’s called that, here’s why:

Like the bramble I talked about in my blackberry picking blog post, it has thorns. They’re not as sharp, but they’re much MUCH longer. Think less hooks, more 3-inch long nails. These are actually twigs that formed shoots straight out from the branches and developed into thorns.

You can find blackthorn in lots of different habitats; the best places are along hedgerows and the outside edges of woods. They like to be in as much sunlight as they can, so these are your best bet. And those are exactly the kinds of places where I searched.

Blackthorns are a pretty big shrub: they can get to 6–7 meters high. If you want to know how to ID them, their thorns are something to look out for. Literally. Blackthorn to the face is not fun.

The leaves are small, slightly tapered at the base, and a little bit wrinkly. They have toothed edges like a saw. Other than that, they’re a standard-looking leaf.

But the most obvious thing to look out for is the sloes themselves. And lucky for me, this year’s been one hell of a year for sloes. They were growing all over the place.

They’re like tiny plums. They’re bluish-black and look like they have ass cheeks.

This one especially:

Fun fact: they’re actually a sister to plums. And just like a plum, they’re a stone fruit. They have a single big seed inside them.

Now this where the similarities stop. Sloes are harder, grittier, and so much more bitter. You bite into one and it makes your mouth feel drier than microwaved rice.

That said, there aren’t many things prettier than a green blackthorn shrub growing bright violet sloes. Gorgeous contrast.

And there was shedloads of them. On some shrubs, the sloes grow in bunches so dense they look like grapes.

While I was picking them, I tried not to pick too many from the same shrub. Taking too much can reduce a shrub’s chance of passing on its seeds and reproducing: the number one reason why plants grow fruit.

I got about halfway through picking when I saw a Reeve’s muntjac deer (Muntiacus reevesi).

It was standing in this shallow ditch on the lefthand side of the footpath. At first, I thought it was a dog. Or someone lost their Build-A-Bear in the woods. These short boys aren’t native to the UK. They were brought here from China during the 20th century.

The one I saw was stood staring at me for a few seconds before he crossed the footpath and bolted into some bushes. He ran away like I just asked him to pay my bills.

Not long after, I finished foraging for sloes; I think I picked around 150 in total. That’s about 300 grams worth (or ~10.6 ounces for folks on the other side of the pond).

From this angle, they look more like blueberries. To me anyways.

I talked to Daniel a couple days earlier and we both thought it was weird how the sloes were ripe this early in the year. Traditionally, they’re only ready to be picked after the first frost. Sometime in September or October.

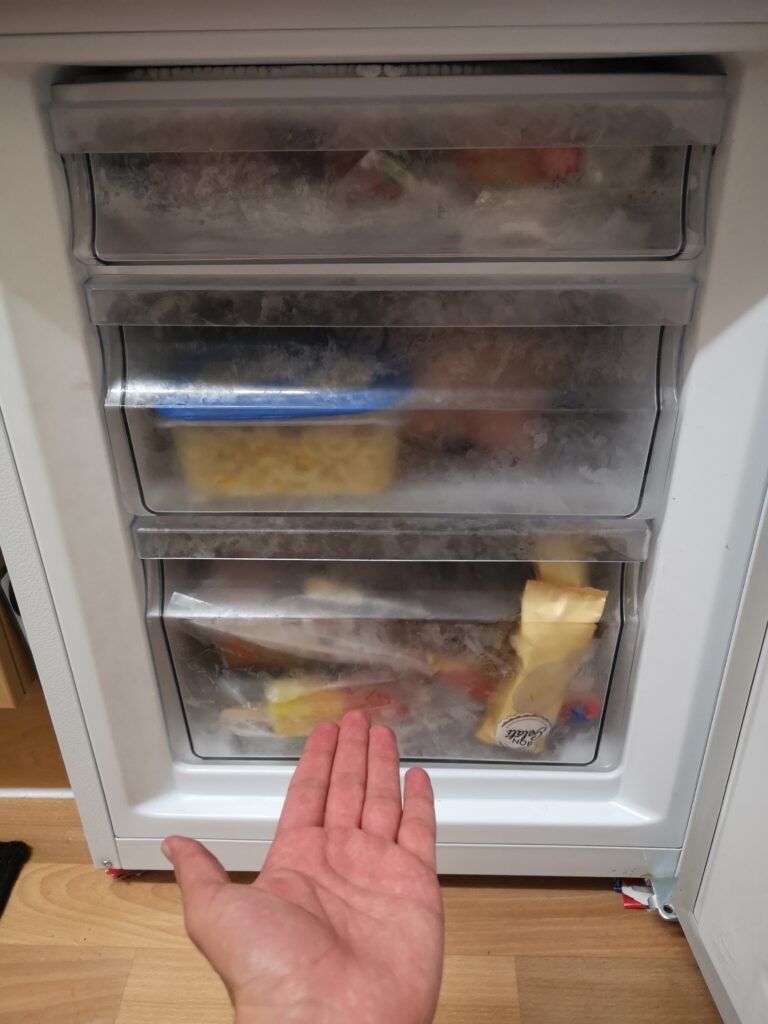

Why after the first frost? It freezes the sloes and that causes their skins to split. At least that’s what people say. I didn’t feel like waiting months for that to happen so I did the other option: I shoved them in the freezer.

You can recreate the same effects of the first frost by leaving them in there overnight. Pro tip: rub them in a bowl with your fingertips (pretend you’re incorporating butter into flour) every 10–15 minutes for the first hour. That should stop them from sticking to each other and forming an iceberg in your freezer. Then when you take them out the next morning, most of them should be loose.

When next morning came, I took them out and waited for them to defrost. But freezing them overnight didn’t really make their skins split as much as I thought it would.

Plan A failed so it was time for plan B. Plan B is less time-consuming, but a bigger hassle. I made a small cut down each of them. Then poured them into one of my mum’s old Nescafé jars she keeps.

Next thing to go in was my fun sauce. I poured in a whole bottle of gin — the full 350 ml. I have no idea what the American version for millilitres is. Please let me know in the comments.

I only used the finest. London Dry Gin…from Tesco.

Then I stirred in 100 grams of granulated sugar; I upped it to 150 after a quick taste test. The ratio of sugar to sloes should be 1:2. If the sugar ratio is any lower, it’ll taste like fruity hand sanitiser. Horrible. Unless you like drinking gin straight. In that case, knock yourself out. Figuratively.

This was before I stirred in the sugar:

This was after I stirred it:

According to the Gin Guide, gin is best kept in a cool, dry place away from anything warm. Cookers, radiators, and even direct sunlight. I’m assuming homemade sloe gin is no different. So I stored mine inside a wardrobe.

As you can tell from the photos, it got a lot darker. In hindsight, I think cutting those sloes open helped their juice infuse into the gin better.

Give it a stir (or just shake it a little) once a day in the first week to make sure the sugar is fully dissolved. After that, you only need to do it once a week…every week…for two months. At least. For me, that’s until late October. But hopefully, it’ll be worth the wait. I’ll keep you guys updated on when I try it. See you guys in the next post. Stay straying!